Fiona Kidman

A very special breed of woman*

A sickly child Fiona Kidman, then Fiona Eakin, was six before she was able to read or write.

Today she’s one of this country’s leading novelists, short story writers and poets. She’s been created a Dame for her services to literature, an OBE preceded it a decade earlier.

In 2006 she was awarded the Katherine Mansfield Fellowship to work on a project in Southern France. The French government has honoured her with the Legion of Honour and a knighthood for services to arts and literature

In this, the year she’s turned 81, she became the inaugural recipient of Otago University’s Irish Writers Fellowship. Her latest book This Mortal Boy won the 2019 Oakham Book Awards fiction prize and the Ngaio Marsh award for best crime novel.

Be proud Rotorua, very proud, for it was here her writing career ignited and the town she called home for 17 years has been the inspiration or setting for at least half a dozen of the 30 plus novels and short stories she’s penned.

It was as a young wife and mum in Lynmore that she wrote her first works – radio plays. They were her self-prescribed antidote to the suburban lifestyle which she admits she found daunting.

“I had come from farms in my early life To put it another way she saw herself as a misfit in suburbia of the mid 20th century.

But let’s put Rotorua on hold for now and step Fiona back to the years that went before, they weren’t easy ones.

Two months after her Hawera birth a specialist declared her near death.

“He told my mother she wasn’t parenting me properly, he admitted me to Wanganui’s Karatane Hospital and ordered her not to come near me until I was better.”

Diagnosed as having a milk allergy it took some months for her to improve sufficiently to be returned to her parents.

“They were penniless, my father didn’t go overseas in the war because he had flat feet but was in camps around New Zealand for a long time.”

She and her mother moved around before settling on her maternal grandparents’ farm near Morrinsville. “She was terrified of being parted from me again.”

Her father came out of the war unwell but with a dream of owning land in a warmer climate.

“My mother had saved money she earned milking cows so there was enough to buy five acres near Kerikeri. It was a great trauma leaving my grandparents, I adored my grandfather who had Alzheimer’s, I never saw him again.”

While her parents waited for the transportable hut they’d bought to arrive they worked as hired help “for grand Raj people out of old China who treated them with disdain.”

By the time she started school the Eakins’ were scratching a substance living out of their unproductive land.

“I found school very difficult, the school found me very difficult, I was known as an odd ball and was bullied for it.”

“I found school very difficult, the school found me very difficult, I was known as an odd ball and was bullied for it.”

She again became ill, this time with pneumonia and glandular fever and was consigned to Kawakawa Hospital.

“This visiting teacher came and discovered I couldn’t read or write, she got a book out of the hospital library and taught me to read in an afternoon, The next week she began to teach me to write, it was a rather painful start.”

The first letter Fiona wrote was to her parents pleading to come home.

“They didn’t have a car but lo and behold they turned up, from then on I’ve always thought writing gets results, especially when I was put in Standard 2 not back in the primmers.”

Within a couple of years she was teaching English to children from Yugoslavia whose parents were working on Northland’s kauri gum fields.

Her secondary schooling began at Kaikohe’s Northland College.

“I was learning French Latin, maths and won the English prize at 13.”

Her stay was brief, an inheritance from her father’s aunts in Ireland was enough for the family to buy a small Waipu farm.

“At Waipu High I had a wonderful English teacher Eileen O’Shea who has reappeared a number of times in my life, She introduced me to poetry but it wasn't enough to keep me at school. I left at 15 and worked in the local drapery store.”

A year in a Morrinsville office followed before Fiona’s Rotorua residency began.

Holidaying here in 1956 the Eakens decided it was the place they wanted to call home, settling in Hannah’s Bay.

Fiona joined the justice department and loathed it.

“It was a chain of human misery I had no idea about and didn’t understand. I saw people in great distress.”

“It was a chain of human misery I had no idea about and didn’t understand. I saw people in great distress.”

She moved to Rotorua Tractor Services, initially as an office girl then into the spare parts department “with Jimmy Crawford, Louise Nicholas’ father.”

Her father had settled into an office job at the then FRI (now Scion) and her mother worked at McLeod’s Booksellers, a shop Fiona still adores.

“One night my mother said there was a job going at the public library that might suit me. I applied, the head librarian Kit Spencer took me on. She was strict but believed in encouraging young women to do well. She saw some potential in the girl who’d left school at 15 and already had two jobs. She turned my life around at the time I was being a bit rebellious. She saw the girl who won the English prize, she was my mentor.”

Fiona swipes aside any suggestion she would automatically become an atypical stuffy librarian.

“I had two lives, my working life where I was a prim little person and the one where I went out with guys who played rugby.”

She and a fellow librarian shared a love of fashion. “We imitated what was emerging from London, sack dresses and stiletto heels. Kit didn’t mind that people came into the library to look at what we were wearing but she did mind about the marks our stilettos made on the cork floor.”

One person who came into the library caught her eye, he was with a group of Standard Two pupils from Rotorua Primary. His name was Ian Kidman.

“I said to my friend Bev ‘see that chap over there?”. She said he looked like Mario Lanza [American signer and film star]. I said ‘I’m going to put my stamp on him’. I pushed my glasses down my nose, strode up to him and said ‘will you keep these children quiet please.’ He just grinned.”

The two saw each other again at a dance.

“He invited me to go for a walk around Sulphur Point. He tricked me into laughing myself silly for an hour with Rudyard Kipling’s story of the Great Green Greezy Limpopo River. He was a great spinner of tales, was Ian.”

She stamped her permanent mark on him when they married a year later.

One of their favourite occupations was going to the movies in what was then the Regent Theatre next to the library in what’s now the Sir Howard Morrison Performing Arts Centre.

“The projectionist was this chap called Bob Harvey, Ian and I became very friendly with him. He managed the place for people called Lightfoot, true to their name they were professional dancers putting on displays at the Ritz Ballroom.

“They’d leave Bob to lock up but instead he’d invite his friends to the premier of the forthcoming movie. We’d emerge out of the shadows and stay at the theatre until the early hours of cold, frosty mornings.”

For those who consider the name Bob Harvey familiar, yes, it is the same Bob Harvey (now Sir Bob) whose teenage years were spent in Rotorua, who went on to make his name in the arts and as mayor of Waitakere city.

When the Kidmans married it was at Ohinemutu’s St Faith’s church. They had developed a close bond with the vicar Manu Bennett (later Bishop Bennett) and his wife Kaa.

While teaching at Rotorua Primary Ian had a second job, that of housemaster at the Maori Apprentice Hostel in Ranolf St in return for free bed and board.

“One of his tasks was to make sure the boys went to Evensong every Sunday. Manu invited him to form the youth club then when I came along he asked me to run the Sunday school, I’ve had a special affinity with St Faith’s ever since.”

When they first married the Kidmans lived in a flat at No 8 Lake Road, opposite the recently demolished Soundshell.

Working two nights a week at the library and being a wife with a husband to care for was a hard ask. Fiona put her hand up when Boys’ High wanted a librarian and was given the job.

“With considerable sadness I left the library. The headmaster, Nev Thornton, was a great sort, an ex All Black. He heard Ian was doing great things with kids who had learning difficulties. He offered him a place on the staff, so for a while we were working together.”

When Fiona became pregnant with their first child, a daughter, the couple made their move to Lynmore. Initially they rented in Iles Rd then bought there. A son joined the family, it was also the birthplace of Fiona’s writing career.

“The judge described my story as being written by probably the dirtiest minded woman in New Zealand.”

“I entered a short story competition run by the Little Theatre. The judge described my story as being written by probably the dirtiest minded woman in New Zealand. It was about real life in a Rotorua rugby football club. I thought obviously that judge knows nothing, clearly I know more about certain aspects of the world than him, it was at this point I realised writing was what I want to do.

“We had absolutely no money so I thought I could earn some by writing. I went to see Ian Thompson, the Daily Post editor. I said I’d worked in the library so how about I wrote their book reviews?

“I wrote a whole page every week for ten shillings a time. I’d use different initials [on the reviews] so it would look like lots of people were doing them.”

She also became a regular Post feature writer and submitted a story to the Women’s Weekly entitled Twenty One Ways To Make Money. “They accepted it and paid me twenty pounds. Ian began to see a certain degree of respectability in what I was doing.”

Her radio plays went on air after she approached local radio personality Helen McConnochie.

“I’d thought about radio as a career when I was at school but the local station manager said I didn’t have the right voice for radio, suggesting instead that I find myself a nice office job.”

With her plays proving popular she began attending workshops and seminars in Auckland and Wellington being mentored by the best in the business. “It was then I really did feel I’d come out of suburbia.”

Around this time Ian was looking to extend his career and had applied for a job at Naenae College but the University of Hawaii intervened.

Its East West Centre approached him to establish a programme similar to the one he’d initiated at Boys’ High.

The opportunity was too good to pass up, he went to Hawaii for three months and Fiona returned to the city’s library.

“I loved being back. People would come in and think I’d just been away on a bit of a holiday but it was ten years since I’d left.”

When Ian returned the move to Wellington was cemented.

“Rotorua was a very formative time for me, the place where I fell in love more than once.”

Prompt her to reflect on her Rotorua years and Fiona reveals her huge fondness for that chapter of her life. “It was a very formative time for me, the place where I fell in love more than once. My novel Songs From The Violet Café is based on when Ian and I washed dishes in the Barbecue Restaurant. I hung out to listen to stories from the Czechosvkian owner Karel (Charlie) Pihera. He’d talk about walking through the forests to escape from the war. My short story The Torch is based on him telling us about a young man who set fire to himself.”

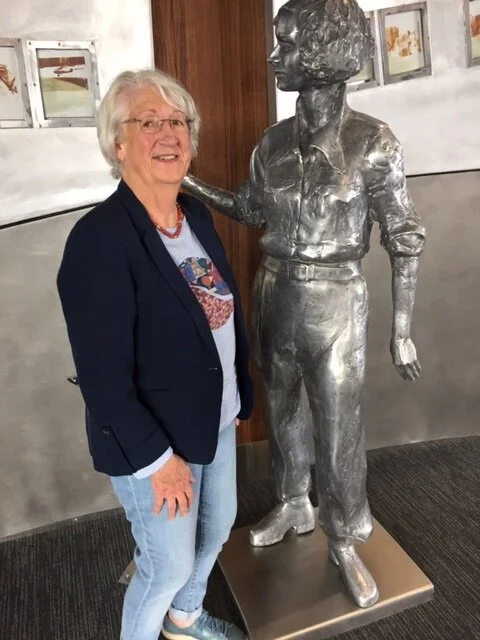

Her book, The Infinite Air featuring Jean Batten, was inspired by Rotorua being the aviator’s birthplace.

“During one of her great disappearances people would come into the library and ask if we had any idea where she might be. This piqued my interest so I set my novel about her based on fact but as a fictionalised, dramatised version of things I thought might have happened to her, there are some things we are never likely to know.”

Unsettled as Fiona felt when she arrived in Rotorua as a teenager and through her early suburban years she pined for the place when she left.

“I missed Rotorua very much, I was so lonely I’d go to Wellington Airport and watch the planes come in just in case someone said ‘hello’ to me when they got off.”

It would be foolish to let this best selling author many times over go without quizzing her about what it is that makes a good writer.

“Being a writer means being a bit of a dreamer, someone who doesn’t mind solitude, I’m both of those at the same time it means being practical, a bit hard nosed and having a belief in oneself. You have to be in charge of your life if you want to succeed and I think I am. But I’m also a family woman and this is an essential aspect of who I am.”

* Dame Fiona Kidman’s A Breed of Women, was acclaimed as influential in changing women’s lives.

Fiona Kidman - the facts of her life

Born

Hawera, 1940

Rotorua then and now

“Rotorua was broad empty streets, an avenue of trees above the railway line where excursion trains ran. There wasn’t a licensed restaurant in town. Well, what fantastic wining and dining I can do now, sitting smack in the middle of those once lonely lanes. Sad about the railway though.”

Education

Kerikeri Primary, Northland College, Waipu District High

On poetry

“For me the power of poetry lies in its rhythm of life, the words spoken and written is spare. Prose flows into different areas but poetry doesn’t give the writer that luxury so there is a tension there.”

Family

Widow since 2017. One daughter, one son. Six grandchildren, five great grandchildren

Personal philosophy

“I believe we can't single handily save the world, but if we can each be a cell of good living in the way we interact with the people we meet along the way in terms of courtesy, kindness and generosity we have a chance of making it a better world.”

Interests

Family, family, family. Reading contemporary fiction. “I love the theatre.” Travel in New Zealand as well as abroad when possible. “Pottering about looking after my 100 year old house. Watching rubbish television.”.